It’s happened so quietly that many people haven’t even noticed it.

Over the past few years, the quality of education that B.C. students receive about Indigenous culture, history and traditions has gotten unprecedentedly better.

Jason Ellis, a historian of education at the University of B.C. calls the change “a Renaissance, a golden age,” for Indigenous education.

And soon the curriculum could get even stronger.

By the 2023/24 school year, any student applying for a B.C. “Dogwood” diploma, also known as a Certificate of Graduation, must have completed at least four of their 80 credits in Indigenous-focused coursework.

“There’s now an understanding that Indigenous education is for all,” said Robert Clifton, the new director of Indigenous Education for Coast Mountain School District 82, whose mother is of Norwegian heritage and whose father is Tsimshian from Hartley Bay.

Indigenous traditions have been taught in many B.C. schools for generations – but until recently, most were designed for First Nations kids, while lessons for non-Indigenous kids were largely restricted to units in social studies, Ellis noted.

“It’s only in the last 10 years that Indigenous education has been integrated across the curriculum,” said Ellis. He said the change is driven by reconciliation, so non-Indigenous kids “learn more about the Indigenous people with whom they live.”

Those lessons now include subjects such as “medicines, traditional seasonal hunting and gathering, processing our foods, talk about colonization and residential school, or cedar and weaving,” Clifton said.

This evolution of B.C.’s education system to include the first peoples of the province has taken 150 years, since 1872 when B.C. established its first public, compulsory, tax-supported schools, which at first were attended by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

Today many Indigenous students in B.C.have the option of attending schools run by their own First Nations, or nearby public schools – but all now include a grounding in Indigenous ways and traditional knowledge.

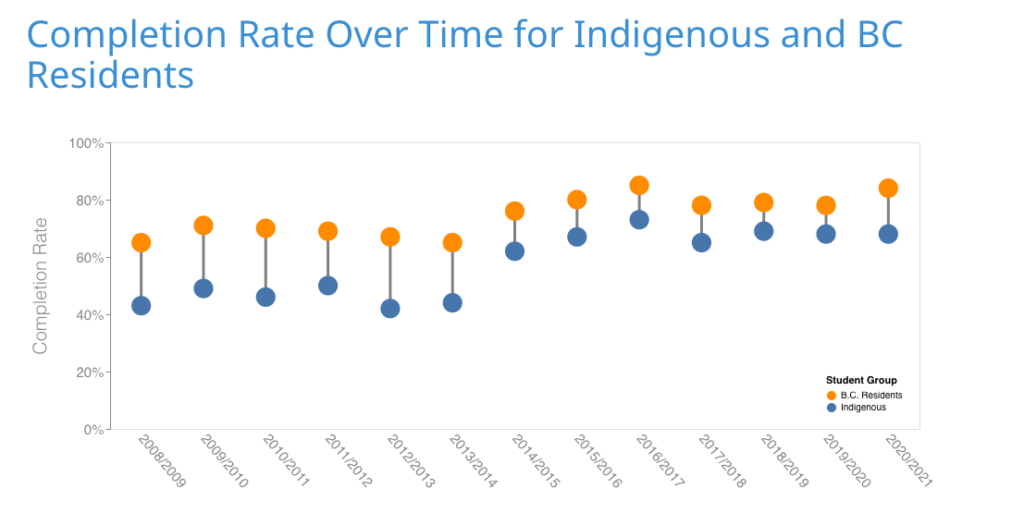

Experts credit the more recent focus on Indigenous education for a dramatic improvement in Indigenous school attendance and graduation rates between 2006 and the last census in 2021.

“The learning we provide students, both indigenous and non-indigenous, has the possibility to contribute to new generations able to live side by side, and do so in a way that honours the histories and cultures of the lands where they’re guests on,” Clifton said.

“That walking together is important,” he added. “All hands are required to do the heavy lifting that is required for us to transform the system, for the betterment of the next generation.”