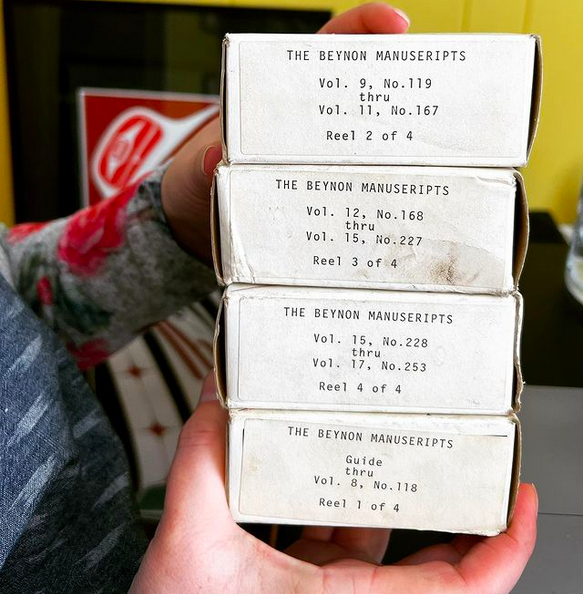

While cleaning a farm shop, you might expect to find things like old tools. Instead, a crew on the Tea Creek Farm in the Skeena region of northwest B.C. found historical treasures–microfilms of Indigenous words from the 20th Century.

The same documents are helping bring back to life lost words in the Sm’álgyax languages of B.C.’s Northwest.

“Check out what our crew found in the workshop,” wrote Jacob Beaton, owner of the farm in Kitwanga, in a social media post. “It is an exciting discovery and reason to double check before throwing old stuff away!”

The boxes contain microfilms of field notes made by famous Tsmishian chief and historian William Beynon, who was hired by the likes of anthropologist Franz Boas and ethnographer Marius Barbeau.

“We are thrilled that the microfilms were rediscovered, that their value was acknowledged, and that they were saved from the trash bin. We hope that the renewed interest in Beynon will lead to more efforts to make his critically important writings more available to Indigenous peoples.”

Jacob Beaton

Starting in the early 20th Century, Beynon was paid by scholars to record conversations with Tsimshian, Nisga’a, and Gitxsan peoples of Northwestern B.C. in the Sm’álgyax languages.

Since finding the microfilm, the farm has learned “that the manuscripts we discovered are being used as part of a language revitalization project,” Beaton said in a statement. “Apparently, they are ‘an absolute gold mine’ for ‘forgotten’ Sm’álgyax words. The stories are being transcribed into modern Sm’álgyax orthography, translated, and then a fluent speaker reads the story in Sm’álgyax, and it is recorded.”

“We are thrilled that the microfilms were rediscovered, that their value was acknowledged, and that they were saved from the trash bin,” said Beaton. “We hope that the renewed interest in Beynon will lead to more efforts to make his critically important writings more available to Indigenous peoples.”

The microfilms are copies of original documents now held in museums in the United States, said Beaton. Digital copies of some of Beynon’s papers can be viewed online on the American Philosophical Society website.

The find on the Tea Creek Farm is “a big deal,” said Chelsea Geralda Armstrong, a historical ecologist who runs her own Indigenous Studies lab in Terrace, 40 kilometres from Tea Creek Farm. “The field notes are in the community, and they can decide what to do with them.”

The historical work of many scholars who studied Indigenous cultures is now read “with a grain of salt,” Armstrong told West Coast Now. As outsiders, they were influenced by their own perceptions and inability to fully understand local languages. But she said Beynon’s work is not questioned, partly because he was both fluent and a member of the community.

“Beynon comes from this really interesting legacy of Tsimshian scholars,” said Armstrong, who is also an Assistant Professor of Indigenous Studies at Simon Fraser University. She explained that these are “fundamentally sound texts” of the “Adawx,” or laws and history of peoples in the Northwest.

Beynon’s father was a Welsh boat captain and his mother was Tsimshian Nisga’a. Born in 1888 in Victoria, Beynon grew up speaking his mother’s language, and later became fluent in other Sm’álgyax languages. When he was 25, he moved to his mother’s territory in the Skeena to inherit his uncle’s title of hereditary chief of the Gitlaan.

For Beaton–whose farm West Coast Now previously profiled– the find has been a mixed blessing. The farm has been deluged with requests from people wanting to see the documents and media wanting to interview Beaton. Now he’s asking everyone to stop calling.

“It’s been overwhelming us, and the timing is bad,” Beaton said in an email to West Coast Now. Tea Creek is a busy working farm, he noted, and “we do not have the capacity to handle the inquiries about the microfilm.”

Beaton’s mother, Patricia Vickers, told CBC she was gifted the reels in 2006 while working on research for her PhD in the U.S. At the time, she did not have access to a machine to view them, and two years ago, she sent them, sight unseen, to her grandsons, Beaton’s children, because of their interest in Indigenous languages.

Beaton said the boxes of microfilm are now in a safe box in a bank. “We are consulting, as time allows, with hereditary leadership, cultural knowledge-keepers, and other Indigenous peoples and considering next steps,” he said.

“If there are any further significant developments with these microfilms or these manuscripts, we will inform everyone over our social media feeds,” he wrote in a statement.