The Mamalilikulla First Nation have had a long journey back to their home territory.

Their people had lived on Village Island or Mimkwa̱mlis on northern Vancouver Island for millennia until they were removed by the federal government, starting as far back as 1914. The land was turned over to industry for logging, while many Mamalilikulla children were sent to the nearby residential school in Alert Bay, leaving a painful legacy.

This history highlights the significance of the recently established Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) the Mamalilikulla declared on their territory in 2021. Based on their traditional laws, they have designated the Gwaxdlala/Nalaxdlala (Lull Bay/Hoeya Sound) area of Knight Inlet – an incredible 10,416 hectares of the central coast – under their protection.

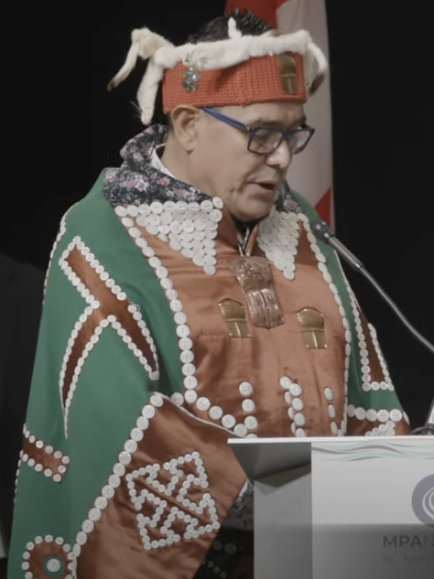

West Coast Now spoke with Mamalilikulla Elected Chief Councillor John Powell on this historic designation and the significance of his community’s return to their ancestral land.

Protected Under Traditional Law

The idea for the Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area first began, Powell told us, as a Marine Protected Area that would conserve the rare coral and sponge species that reside in Gwaxdlala/Nalaxdlala.

“When I was elected, I didn’t think that went far enough,” Powell told us on the decision to expand their mandate beyond the ocean. “Industry has decimated the land, the sea, and the skies. We had to protect more than a marine area.”

“So under our ancient law, we made a declaration for an Indigenous Protected Area in order to restore the elements back to their natural state,” he said. “We’ve been working tirelessly over the past couple of years.”

Unlike a federally-mandated Marine Protected Area, Mamalilikulla First Nation independently declared the IPCA designation according to their constitutionally enshrined Indigenous Rights.

Following this, they invited provincial and federal governments to participate in a collaborative governance approach to the area, resulting in the marine component becoming a proposed site for the Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area Network.

The new IPCA will cover the unique coral and sponges, plus 240 different marine species and a portion of their land, including three watersheds. The declaration aims to “protect, restore, and maintain unique habitat and culturally significant species,” ensure the Mamalilikulla First Nation’s food security, and preserve important archaeological and cultural sites.

“In terms of reclaiming our traditional territory, it’s extremely important,” Powell said.

Returning to the Land

A new video released by the Mamalilikulla First Nation underscores the region’s stunning beauty and makes a compelling case for its conservation. Footage shows the celebration of the IPCA declaration that took place in the area on May 5th, 2022. Elected and hereditary leaders, elders, singers, dancers, and guests gathered for the community event in honour of their renewed connection to their territory.

The event was clearly powerful for many dispersed members of the Mamalilikulla First Nation who had never visited this part of their land before. “It’s been at least 100 years since this part of the territory has had any dancers on it or songs sung in this space,” says Chief Dr. Robert Joseph in the video.

Powell believes the impact of the IPCA declaration will be widespread for this recovering ecosystem. In 1920, the Mamalilikulla counted 26 salmon in their three watershed areas. Last year, he remarked, they counted 500 pink salmon in the mouth of a single watershed.

“We know that when industry no longer has the ability to interrupt natural processes, without even doing restoration, [salmon] numbers increase. We know that’s going to be the result of our protected area,“ he stated.

Guardians of the Future

The Indigenous Coastal Guardians are an integral part of the IPCA’s success, but they have a considerable job ahead of them. Their responsibilities include monitoring the large region, conducting stream surveys, cleaning log jams, and tracking salmon, bears and other wildlife populations.

Powell is concerned that Mamalilikulla Guardians don’t yet have the capacity to properly monitor and protect the designated area.

“Our Guardians, like all Guardians, are severely under-resourced. Funding was not specifically put aside for the program in a sustainable way, so funding for those Guardians is really piecemeal,” he remarked.

Another concern he has is their ability to enforce their laws. “They can advise people in our territory, tell them that there are fish closures, or that they are not permitted in the area, but the mechanism to enforce, that is not there. Both those things we are working on to find some resolution for.”

“We know that when industry no longer has the ability to interrupt natural processes, without even doing restoration, [salmon] numbers increase. We know that’s going to be the result of our protected area,“ he stated.

Responsibility for the Land

The answer to the capacity question, Powell hopes, will be found in additional funding from external non-profits that recognize the importance of environmental conservation and Indigenous stewardship.

“We know that the government has limited ability to help us. We are hopeful that philanthropic non-governmental organizations will provide resources that are necessary to carry on the restoration that needs to be done,” he shared.

“We were put in this place as Mamalilikulla people, and we have laws that bid us to care for the land, the sea and the sky,” Powell told us.

“People may agree or disagree with what we are doing – that’s not important. What’s important is that we take responsibility for the land, the sea and the sky, and we act on it. And that’s what we are doing.”