Pacific herring were abundant on BC’s coast for millennia but have been in steady decline over the past century due to rampant overfishing. Now, some experts are calling for a last-minute moratorium on the Food and Bait Fishery ahead of its upcoming opening on November 24th. Advocates like Pacific Wild, a conservation organization focused on the Great Bear Rainforest, have been raising the alarm for years about the critical stocks disappearing across the Strait of Georgia. They are worried that herring populations might not recover without immediate action from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, though critics, including some First Nations, say these concerns are overblown.

Keystone Species

Herring are a forage fish and a keystone species in the coastal food web. In early Spring, as they migrate ashore to spawn, all kinds of animals, from seals, sea lions, and salmon to humpbacks and grizzly bears, feed on the richness of herring and herring roe. At this time, commercial fisheries harvest them from B.C. waters and primarily sell them to Japan, where herring roe is a delicacy. The unused fish remains, about 90% of the harvested biomass, are then used as food for pets and fish farms. This is a different herring fishery from the Food and Bait Fishery.

“Our stance at Pacific Wild is we would like to see a complete (coast-wide) moratorium on Pacific herring in B.C. until our stocks have had time to recover.”

Sydney Dixon, marine specialist at Pacific Wild

Sydney Dixon, a marine specialist at Pacific Wild, thinks not enough is being done to protect this crucial fish in our waters. “Our stance at Pacific Wild is we would like to see a complete (coast-wide) moratorium on Pacific herring in B.C. until our stocks have had time to recover,” said Dixon to the North Island Gazette in a recent interview. “They’re at such a low biomass and spawning state right now.” Dixon went on to say that herring populations can fluctuate any given year, and climate change has made them particularly unstable, but overfishing was undoubtedly the primary cause to blame.

Declining Stocks

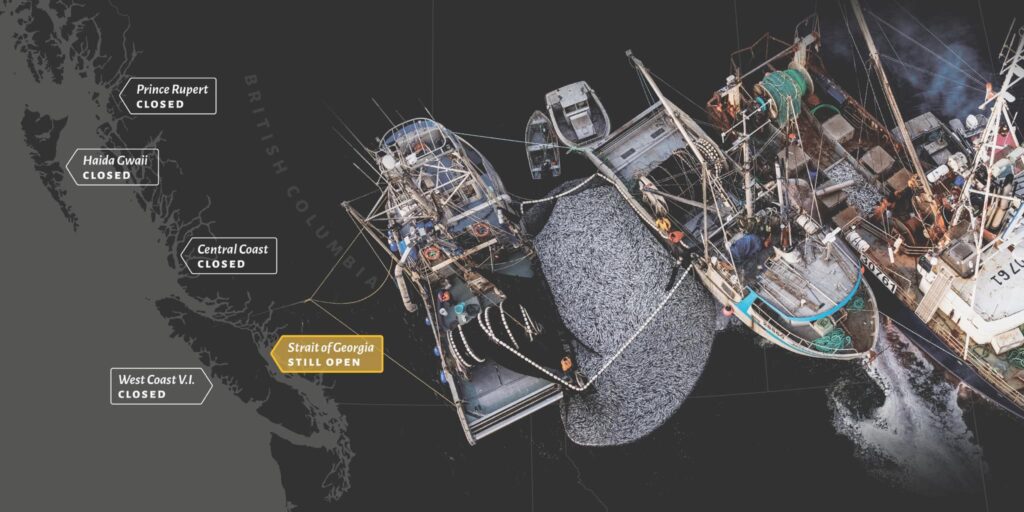

Four of the five major herring populations in BC, including Central Coast, Haida Gwaii, Prince Rupert, and West Coast Vancouver Island, have been closed to herring fishing. The Strait of Georgia herring stock is the last remaining of five stocks on the West Coast. In 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) reduced the herring harvest rate from 20% to 10% within the Strait of Georgia to sustain the struggling populations. Then-Minister Joyce Murray said at the time: “Herring are vital to the health of our ecosystem, and the stocks are in a fragile state. We must do what we can to protect and regenerate this important forage species.”

Despite the decreased harvest rates, herring fisheries’ are not reaching their allowable quotas, suggesting that there just aren’t enough fish in the water. In the 2021-2022 spring season, the DFO set the quota at 7850 tons, yet non-Indigenous fishers only caught 3407 tons. “Looking ahead to 2023, spawning biomass in the SOG [Strait of Georgia] is projected to decline an additional 13% from 2022,” Pacific Wild reported.

Indigenous Harvesting

Herring and herring roe have been essential to First Nations food security for millennia. Traditional harvesting methods are also more sustainable compared to the spring commercial fisheries that kill the whole fish for their eggs, reducing the number of viable spawners. The Indigenous practice of only collecting “spawn on kelp” – the roe collected from kelp or branches – permits fish to spawn again and sustain the population for future years.

“An (indefinite) moratorium would decimate the First Nations involved in these fisheries. If we were seeing a decline, I would definitely be saying something … but these are the best (herring stocks) I’ve seen in 30 years.”

Ronnie Chickite, elected Chief of the We Wai Kai Nation

In the face of calls for a moratorium, some Indigenous fishers are, in fact, arguing that the herring fisheries have never been better. Speaking to the North Island Gazette this month, Ronnie Chickite, elected Chief of the We Wai Kai Nation and herring fisherman, pushed back against Pacific Wild’s comments and said a moratorium would hurt First Nations economies. “An (indefinite) moratorium would decimate the First Nations involved in these fisheries. If we were seeing a decline, I would definitely be saying something … but these are the best (herring stocks) I’ve seen in 30 years,” he said.

But First Nations who rely on herring harvests are not a monolith. The W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council has been outspoken about the need to close the Strait of Georgia fishery to give the stocks a chance to rebuild. “We hear of a few people getting herring, but never enough to sustain their families […] We see that all the other sealife is starting to deplete also. That was a part of our treaty, that we’d be able to fish and hunt […] to carry on our life as we did before,” said Eric Pelkey, Hereditary Chief of Tsawout of the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation, near Saanich. In 2019, the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council sent letters to DFO requesting a moratorium in the Strait of Georgia but heard no official response.

Other First Nations have taken dramatic measures to close their territories off from commercial herring fishing. The Heiltsuk First Nation has prohibited all commercial harvesting of herring in their waters after a struggle with DFO in 2015. In 2022, the Kitasoo Xai’xais declared Kitasu Bay near Klemtu an Indigenous Protected Area, only allowing Nation members to harvest roe using sustainable methods to feed their communities.

The Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations has also seen herring decline in their harvesting area near Port Hardy. In 2021, they took action and filed an injunction in federal court demanding that DFO halt commercial herring spawn on kelp licences in their traditional territories. It did not succeed, even though DFO scientists’ subsequent reports confirmed the declining herring numbers in the region. “Once again, Western science experts have verified the accuracy of our traditional knowledge – the herring were simply not there,” said Chief Paddy Walkus at the time.

Future Leadership

Despite the debate, all parties seem to agree that it’s time for First Nations to lead the decisions about the future of herring fisheries. “(People) need to trust Indigenous knowledge and understand the rights of Indigenous people as we are the stewards of the lands and ocean. (It’s our priority) to maintain sustainable stocks (for the benefit of) the overall ecosystem,” Dixon of Pacific Wild told the North Island Gazette.

“DFO is committed to managing Pacific herring fisheries to ensure that there are enough herring to spawn and sustain the stock into the future and support its role in the ecosystem.”

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)

Meanwhile, DFO says it continues to monitor and enforce conservation measures in consultation with First Nations, commercial fisheries, and scientists. “The stock in the Strait of Georgia is not considered overfished, nor is overfishing considered to be occurring,” DFO said in a statement earlier this year, adding that the herring biomass fluctuates in the Strait of Georgia depending on a variety of factors. “DFO is committed to managing Pacific herring fisheries to ensure that there are enough herring to spawn and sustain the stock into the future and support its role in the ecosystem,” they said.