The largest estuary restoration project to ever take place on Vancouver Island is currently underway, though not without controversy. The Cowichan Estuary restoration project intends to revitalize 70 hectares of marsh habitat to restore biodiversity and make the shoreline more resilient in the face of climate change. The project is a partnership between the Cowichan Tribes, Nature Trust of British Columbia, and Ducks Unlimited Canada, with support from the provincial and federal governments. However, their plan has unexpectedly drawn out some critics hoping to make the estuary a lightning-rod issue for climate change denial.

We spoke to Tom Reid, the West Coast conservation land manager for the Nature Trust of BC, about the scope and vision of the project, and why he feels optimistic that the estuary’s restoration will benefit communities for generations to come.

“If we don’t have estuaries, there’s going to be a collapse of Pacific salmon stocks, and nobody wants that.”

Tom Reid, West Coast conservation land manager for the Nature Trust of BC

Essential Ecosystems

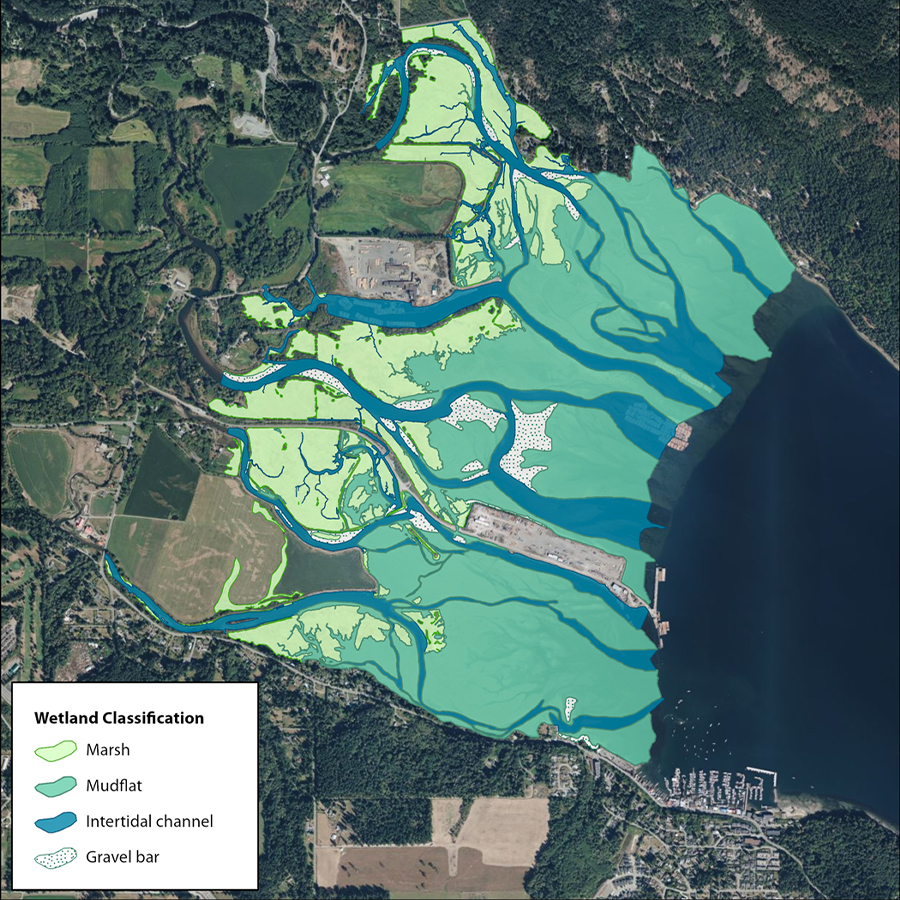

The Cowichan Estuary sits beside Cowichan Bay on the territory of the Quw’utsun people (Cowichan Tribes) at the southern end of Vancouver Island. The area is an intertidal zone where the Koksilah and Cowichan rivers meet the Pacific Ocean, and together, they create the salty marsh ecosystem that hosts abundant wildlife.

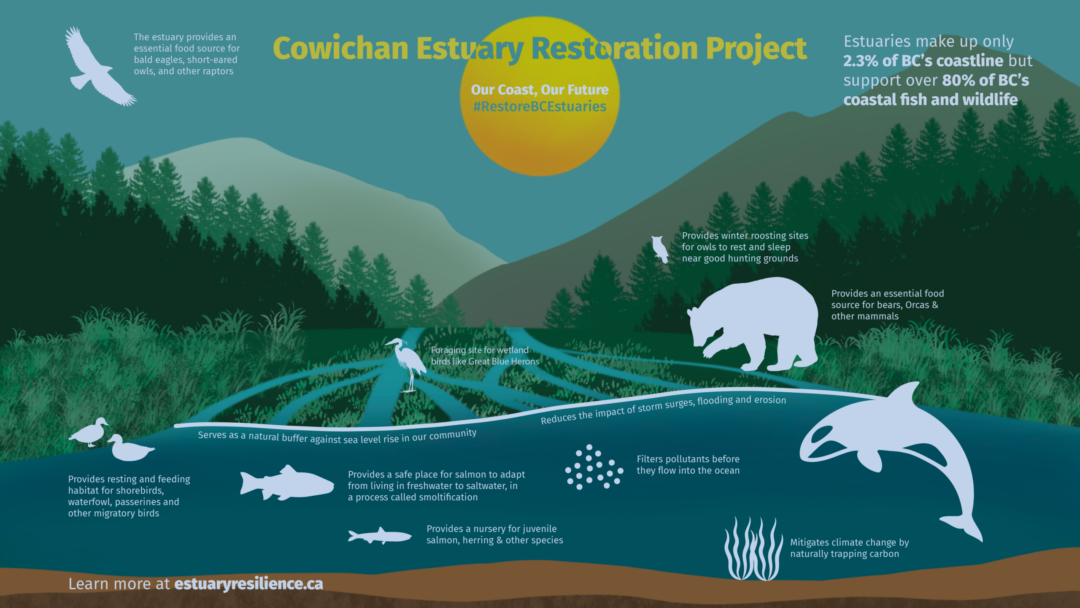

Estuaries like this one are some of the world’s most productive ecosystems and are critically important for maintaining biodiversity. Though estuaries only make up 2.3% of BC’s coastline, they support 80% of all fish and wildlife, from Pacific salmon and grizzly bears to bald eagles and Dungeness crab. The Cowichan area alone provides habitat and breeding grounds for up to 230 bird species. This estuary is also a sanctuary environment for juvenile salmon to feed and grow before reaching the ocean, which maintains healthy populations.

“There’s such a narrow band of elevation where these ecosystems thrive, but when you get this huge mixing of upland and marine nutrients, that obviously attracts a ton of fish and wildlife in these estuary ecosystems,” Reid explained. “If we don’t have estuaries, there’s going to be a collapse of Pacific salmon stocks, and nobody wants that.”

Estuaries are also vital in natural climate change mitigation, acting as storm barriers, pollutant filters, and carbon absorbers. Salt marshes are powerful ‘carbon sinks’ – where plants like kelp accumulate carbon dioxide in their roots, stems, leaves, and the surrounding sediment. Estuary sediments can capture this blue carbon up to ten times faster than forest soils.

Restoration Underway

“By removing these other berms and flattening [them] down, we’re slowing the water down and actually giving it more of an ability to deposit nutrients and sediment.”

Tom Reid

Reid and a team of scientists have been closely monitoring the Cowichan Estuary over the past several years. They have partnered with First Nations up and down the coast to research the landscape’s resilience in the face of rising sea levels and increasing impacts of climate change. “We collected years and years of data with Cowichan Tribes and analyzed it … and it was coming back that the Cowichan Estuary is actually drowning. Basically, it’s not able to survive,” Reid told us.

Their modelling concluded that 60% of the marsh area will be lost to rising sea levels by 2100 if the restoration was not undertaken. “All our data and monitoring is showing that we have to change the land use, to do this restoration, and refocus the food system that the land can provide and support,” he said.

From there, Reid and his team identified four aspects of the restoration process to enhance the resilience of the estuary for fish and wildlife on farmland purchased by Nature Trust of British Columbia and Ducks Unlimited Canada in the 1980s. To begin with, they have begun the initial process of removing two kilometres of dikes and berms from Dinsdale Farm and Koksilah Marsh, some built as far back as the 1800s.

“By removing these other berms and flattening [them] down, we’re slowing the water down and actually giving it more of an ability to deposit nutrients and sediment,” Reid said. The other components of their two-year plan include creating intertidal channels, reconnecting areas cut off from the tide, and restoring marine riparian and flood fringe forests.

“This would actually build this resilient capacity into the system to actually enable the Cowichan to give it a better chance to survive for longer, and to still provide that habitat for juvenile salmonids, Dungeness crabs, shellfish, migratory birds,” he stated.

Food Security

Reid and his team have been collaborating with the Cowichan Tribes and Dr. Jennifer Grenz from UBC’s Indigenous Ecology Lab to ensure this landscape continues contributing to sustainable local food systems. This includes doing everything from supporting the best plants for fish and wildlife habitats to ensuring the water remains nutrient-rich.

“It’s not just a restoration – [Dr. Grenz] would call it ‘fortress restoration’ – where we’re going to restore, and nobody’s allowed to come and touch anything. This other perspective is this is a food system revitalization for medicines and culturally significant plants and fish and wildlife,” Reid said.

Prior to colonial contact, the Cowichan Estuary was home to three traditional Quw’utsun villages known as Khenipsen, Comiaken, and Clemclemuluts. Dr. Grenz’s research has shown that historically, local Indigenous communities used an economic model akin to commercial production; rather than a hunter-gatherer model, they were harvesting for trade and feeding thousands of people.

The arrival of settlers brought deadly disease – it is estimated that 90% of the Cowichan peoples were killed in a smallpox epidemic in 1862. Their land was stolen by the colonists and turned into farmland, and later, forever altered by industrial use, including logging, shipping and commercial fishing. Dr. Grenz notes that the estuary rehabilitation process that is underway is “food systems reconciliation.”

“We’re trying to provide that education and the opportunity to see, once the project starts, that there are examples from around the world of restoration having those benefits to the overall community,”

Tom Reid

“It’s more important for us to be like, let’s actually make it a meaningful partnership that’s collaborative,” Reid said, speaking of the alliance with Indigenous ecologists and experts. “It becomes more about relationship-building than just, ‘here’s the science, here’s the restoration, we’re done’ kind of thing. It’s probably one of the most exciting parts of the overall project up and down the coast.”

Climate Deniers

In an unexpected turn of events, a local right-wing contingent seems to have zeroed in on the estuary as a focal point for their wider concerns. The newly formed group, the Land Keepers Society, held a town hall meeting in August with the intention of stopping the project. An investigation by The Breach found the Society had “partnered with a group of local organizers and aspiring politicians who push far-right climate denial conspiracy theories,” noting that “they appear to be using the local estuary restoration project to create opposition to climate action.”

The group seems primarily concerned about the conversion of farmland for the project, even though the land was purchased by the Nature Trust partnership back in 1985. Reid understands the general anxiety expressed in the town hall meeting but is quick to point out that the land is being used to ensure it yields more and through more sustainable methods. “I think there’s an immediate reaction, like ‘we’re losing farmland, or we’re losing food security.’ When actually, it still is producing food. It’s just a different type of food system,” he said.

“The health of these ecosystems represents the health of our coastal communities and [determines] whether or not the coastal communities are going to be resilient.”

Tom Reid

Reid said he’s optimistic that once people see the results of the estuary’s restoration, they will come on board. “We’re trying to provide that education and the opportunity to see, once the project starts, that there are examples from around the world of restoration having those benefits to the overall community,” he said.

Some locals have also protested the loss of a popular walking trail along the dike, though the trail itself is located on private land owned by the partnership. The public will still have access to the land through Maple Grove Park and a forthcoming trail network, including an Indigenous interpretive trail. There will also be a viewing platform established for birdwatching and more. If there are still concerns, Reid invites the public to reach out. “If you write us a note or give us a call, ask us questions, we’ll respond,” he said.

For the Community

Reid reiterated that his coalition of partners has done diligent research through extensive modelling, consulting, and relationship-building over the years to develop a restoration strategy for the Cowichan Estuary. “The health of these ecosystems represents the health of our coastal communities and [determines] whether or not the coastal communities are going to be resilient,” he explained.

He feels confident that the estuary will have widespread benefits from sustainable food harvests to fortified shorelines that can withstand rising sea levels and protect coastal communities for generations to come. “I think we all have pretty much the same values when it comes down to it. We all want clean water. We all want resilient communities and ecosystems. No one’s going to argue with that,” he said.