Groundbreaking new research is shedding light on the long-extinct woolly dog that used to live among the Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest. Bred for its thick woolly hair, used in weaving blankets, the unique woolly dog was domesticated by Coast Salish communities pre-contact. Researchers have now been able to sequence the woolly dog’s genome to understand more about this distinctive species lost due to colonialism.

We spoke with Debra Sparrow, co-author of the study and master weaver from the Musqueam First Nation, about her ancestral relationship with the woolly dog and its cultural significance, evident to this day in her own weaving practice.

Smithsonian Calling

Sparrow was first approached by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, a researcher of Coast Salish weaving practices, who was working closely with a team of scientists out of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. The team had uncovered the pelt of a small white woolly dog named Mutton in the Smithsonian collection, believed to have been from Stó:lō Nation territory in the present-day Fraser Valley.

The dog was adopted in 1858 by settler naturalist and ethnologist George Gibbs, who kept detailed records of Mutton’s life. The canine was “the only known example of an Indigenous North American dog with dominant precolonial ancestry” living after the arrival of the Europeans. As a result, not much was known about the woolly dog in the scientific community, aside from what was written in journals of colonisers.

For example, Captain George Vancouver took note of them upon his arrival on Coast Salish territory, writing in 1792, “They were all shorn as close to the skin as sheep are in England; and so compact were their fleeces, that large portions could be lifted up by a corner without causing any separation.”

“Survival of the woolly dogs depended upon the survival of their caretakers in addition to disease, expanding colonialism, increased cultural upheaval, displacement of Indigenous Peoples and diminished capacity to manage the breed.”

Lin et al in Science

Researchers at the Smithsonian wanted to know if Mutton was a pure woolly dog and, if so, how unique his genetic makeup was from European dogs. What could he tell us about the origins of these unique animals in Coast Salish society?

By sequencing his DNA from the pelt, they found Mutton was 84% woolly dog and 16% European canine breeds. Scientists determined that he shared just one gene related to long hair with contemporary canines. This discovery was significant for them because it meant that “the wooliness of the Coast Salish woolly dog is unique,” according to Logan Kistler, Smithsonian anthropologist, paraphrased in Hakai magazine.

The scientists concluded that the rest of the woolly dogs quickly went extinct once settler contact was made. “The Survival of the woolly dogs depended upon the survival of their caretakers in addition to disease, expanding colonialism, increased cultural upheaval, displacement of Indigenous Peoples, and diminished capacity to manage the breed,” the publication noted.

Cultural Research

In addition to the genetic research, Hammond-Kaarremaa led a group of Indigenous cultural advisors to share traditional stories through oral story-telling about the woolly dog’s presence in West Coast communities. Sparrow was one of this group, composed of weavers, Knowledge Keepers, and elders who shared passed-down stories of the woolly dog going back at least 1800 years, and possibly even 4000 or 5000 years.

“It’s reached the scientific community, which I’m excited for because it’s what we’ve always known,” Sparrow said. She commends the way the scientists approached their scientific research while incorporating traditional Indigenous stories to “put those two amazing knowledges together.”

“They are respectfully saying, ‘let the Indigenous people, who this little being came from, tell the story. We’re going to be secondary to this,’” Sparrow commented. “So I honour that because they’re not wanting to run with the story. They’re saying, ‘Please reach out to all the villages where you can find information and stories.’”

Ancestral Weaving

Sparrow had first heard about the woolly dog from her grandfather, Chief Ed Sparrow, who grew up among the creatures and the weavers who spun their wool into yarn. “He shared with me everything that he knew and saw, and I was in awe of him,” she told us.

However, he didn’t speak about traditional weaving until she asked him directly. This cultural practice was one of the “missing pieces that residential school made sure were put aside, that our elders and parents didn’t share or teach us because, of course, they thought it would never be something of value to us anymore because of colonialism and assimilation,” she explained.

When she asked him why he had never mentioned it before, he told her, “‘Well, they told us not to teach you guys anything because you’d never use it,’” she shared. “I said, I am now, and I want to know everything.”

Her grandfather explained that their people used to have a domesticated animal whose white wool-like fur was used for making blankets—”this little thing, a little bit smaller than a fox.” They were kept in pens like sheep and cattle and often isolated on small islands where they were fed and tended to.

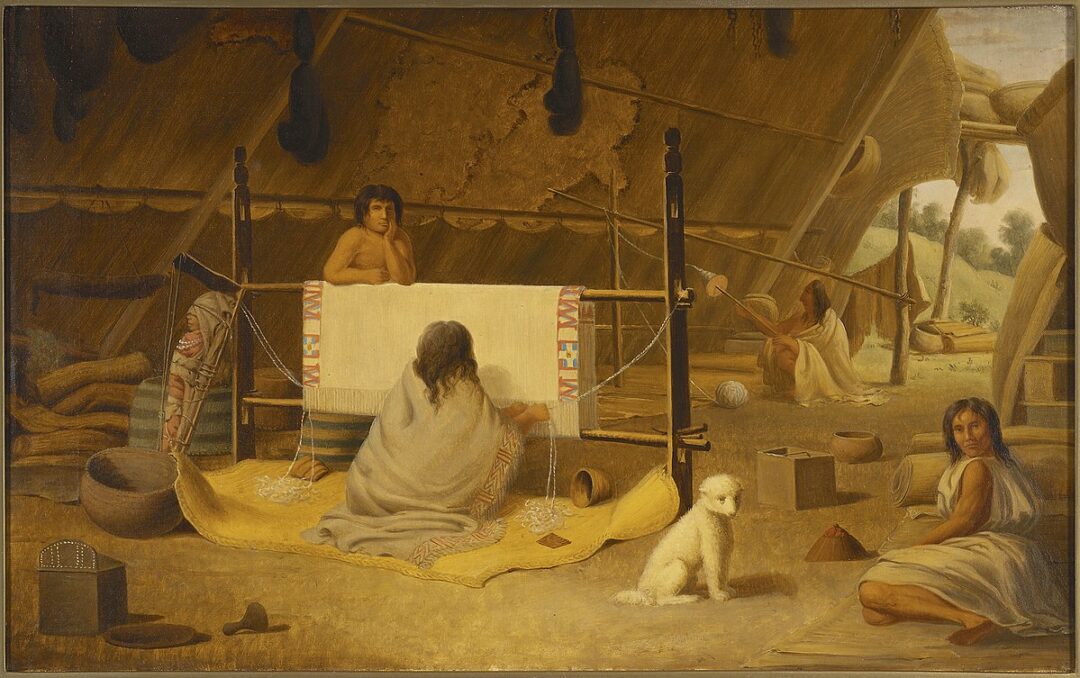

The woolly dogs’ fur was then sheared and mixed with mountain goat hair, clay, and stinging nettle fibres to weave into blankets and garments. Sparrow noted the immense dedication and time it would take to weave with these materials. “Imagine how long it took them to make one. But then, of course, they weren’t working alone. It was a family thing,” she said.

“To be a weaver is not just about making a pretty blanket. It’s about ceremony. It’s about teaching ourselves. It’s all about the math – putting a blanket together with patterns. It’s about art.”

Debra Sparrow

Chief Sparrow told her he recalled his own grandmother and three to four other women gathering around and weaving together, working out of a shed behind the main house. The women would work, layer by layer, intricately preparing the fibres for weaving. He remembered they were working on his regalia for his naming ceremony, which would take place at his great-grandfather’s longhouse.

“He said after that, he never saw any more weaving again until he saw us,” Sparrow said. “I was so grateful for that because he was about 83 or 84 then, and he was there with me and sharing this oral passing on of tradition.”

New Traditions

Sparrow is now working on an updated version of a woolly dog blanket using modern canine fur – the first of its kind in 200 years. “I was overwhelmed with the thought of making one of those, and I thought, maybe someday in the future, I might think about it,” she said. “Now it’s 30-some-odd years later, I felt maybe I’m ready to challenge this.” She was also just awarded a prestigious Canada Council for the Arts grant for her historic weaving project.

“To be a weaver is not just about making a pretty blanket. It’s about ceremony. It’s about teaching ourselves. It’s all about the math – putting a blanket together with patterns. It’s about art.”

But Sparrow said she doesn’t consider herself an artist. “I consider myself a woman who is totally reflecting what we would have been doing pre-contact. It’s about life,” Sparrow said. “It’s about the fabrics and the fibres we use to create our everyday lives.”

The contemporary practice of Indigenous weaving is also an important part of reconciliation, she noted. “I’ve been doing this work, and it’s allowed my light to shine,” Sparrow told us. “I want to shine a light on everybody – I want everybody’s light to come back – and I feel like the woolly dog is a part of this.”