Radha Agarwal, Local Journalism Initiative, The Northern View

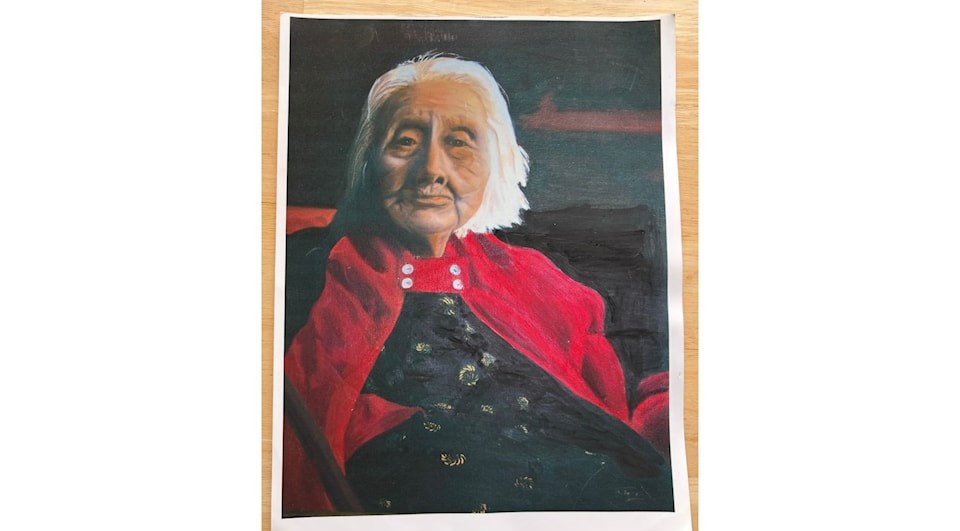

At 92, a Skidegate-based artist exemplifies resilience as she writes an instructional book, “Crochet for the Blind,” and teaches swing dance lessons this fall.

After losing her eyesight five years ago, Dolores Davis—who says she is the second oldest person in her village—continues to defy expectations by jogging every day.

Throughout her life, she produced landscapes, seascapes, portraits, and embroidery, many of which were displayed in museums in Haida Gwaii, Prince Rupert, and Vancouver.

“The only art I can still do is crochet and make paper flowers, which I use at funerals,” she said.

In fact, she was stepping out for a friend’s funeral as she spoke.

“Most of them are younger than me,” she added.

Her sister-in-law is currently the oldest person in the village, four years older than her.

“I did all the plans, and then I made it, and like I usually say, no man will ever corner me again.”

Dolores Davis

“My grandmother lived to be 109 for her grandchildren,” she said proudly.

Dolores said she has always been active; when she returned to Skidegate in the 1980s to live, she built much of her house herself. From installing the roof to laying the flooring and crafting the chairs and upholstery, she reflects on that deep connection one felt while building one’s own home in those days.

“I did all the plans, and then I made it, and like I usually say, no man will ever corner me again.”

Being away from the homeland

“I had quite a time in Prince Rupert with my first husband, and here he was going out with other women while I was at home, and he whacked me one in the face, so I had a big bruise,” she said.

“He tried to come back, and I said, ‘No,’ I figured he does it once. He’ll do it again.” And then she never looked back.

“He came home one day and said, ‘Dolores, I’m leaving you.’ And I said, ‘Okay, I’ll help you pack.’”

Dolores Davis

Her second marriage took her to Smithers in 1963, where she stayed for almost 15 years. There, Dolores worked as a payroll accountant.

“He came home one day and said, ‘Dolores, I’m leaving you.’

“And I said, ‘Okay, I’ll help you pack.’”

Her son with him was three months old at that time. He is now 60.

She now thrives in her single life.

Unfortunately, Dolores had to stay away from Haida Gwaii after marrying because, until 1985, Indigenous women would lose their status if they married a non-indigenous man.

In those days, Haida Gwaii society did not allow women who married white men to stay in the village overnight.

“Because my skin was dark, I wasn’t white. I was an Indian, but I was not.”

Dolores Davis

In the documentary “The Woman Who Returns,” she said this rule made her feel like she did not belong anywhere.

“Because my skin was dark, I wasn’t white. I was an Indian, but I was not,” she said.

She stayed away from home for almost 40 years before returning in 1986. Dolores, who is from the Raven Clan, maintains a close relationship with the language. She is a Haida speaker because of her grandmother.

Continuing obstacles

She reflects that her oldest son, who was a chef, died of cancer and from that she has developed a simple coping strategy.

“Accept it. I have learned to accept things the way they are. I look at situations and if I can’t change them, I accept them just the way they are.”

Dolores is currently trying to improve the degeneration in her eyes. To do so, she has to travel from Haida Gwaii to Vancouver because such eye care services are unavailable on the remote archipelago.

“Macular degeneration is happening too fast; the treatment slows it down,” she said.

She must make this long journey to Vancouver every six weeks. However, she finds this to be a significant improvement from the beginning of her treatment, when she had to travel there every two weeks.

Her words carry a certain lightness and a touch of optimism as she chuckles and discovers the silver lining in everything life presents her with.