The first shift begins on a dirt path.

The women walk toward the cannery at Kimsquit Inlet, aprons tied against their waists, scarves pulled tight against the morning air. One carries a child. A few glance sideways. Most look straight ahead.

The photographer, Harlan Ingersoll Smith, was an anthropologist travelling the Central Coast documenting communities. By 1920, canneries had become part of what Smith understood as a transitional frontier world—places where Indigenous land, immigrant labour, and industrial capitalism collided.

For decades, British Columbia’s salmon canneries ran on mornings like this—on people showing up season after season, often far from home, to do work that had to be done quickly and without pause once the fish arrived.

A Coast Organized Around Salmon

From the late 1800s through the early twentieth century, salmon canneries spread rapidly along BC’s coast. Plants were built at river mouths and sheltered inlets so fish could be processed immediately after landing. By the early 1900s, salmon canning had become one of the province’s largest industries.

Canneries were not just industrial sites. They were seasonal towns, complete with worker housing, bunkhouses, cookhouses, stores, and docks. Their populations expanded and contracted with the salmon runs.

Labour was structured along racial lines.

Indigenous people worked as fishers, net menders, tenders, and processors on their own territories. Chinese labourers were channelled into some of the lowest-paid and most dangerous jobs, including butchering, heavy machinery operation, and can soldering. Japanese immigrants, many of whom had fishing experience, became central to both fishing fleets and cannery floors.

Women were relied upon for processing work because of their perceived speed and endurance. They appear repeatedly in cannery records, though rarely in their own words. They cleaned, cut, filled, packed, and labelled salmon for hours at a time, often standing in cold water on concrete floors. When runs were strong, shifts stretched late into the night. When runs failed, wages vanished.

A Family Affair

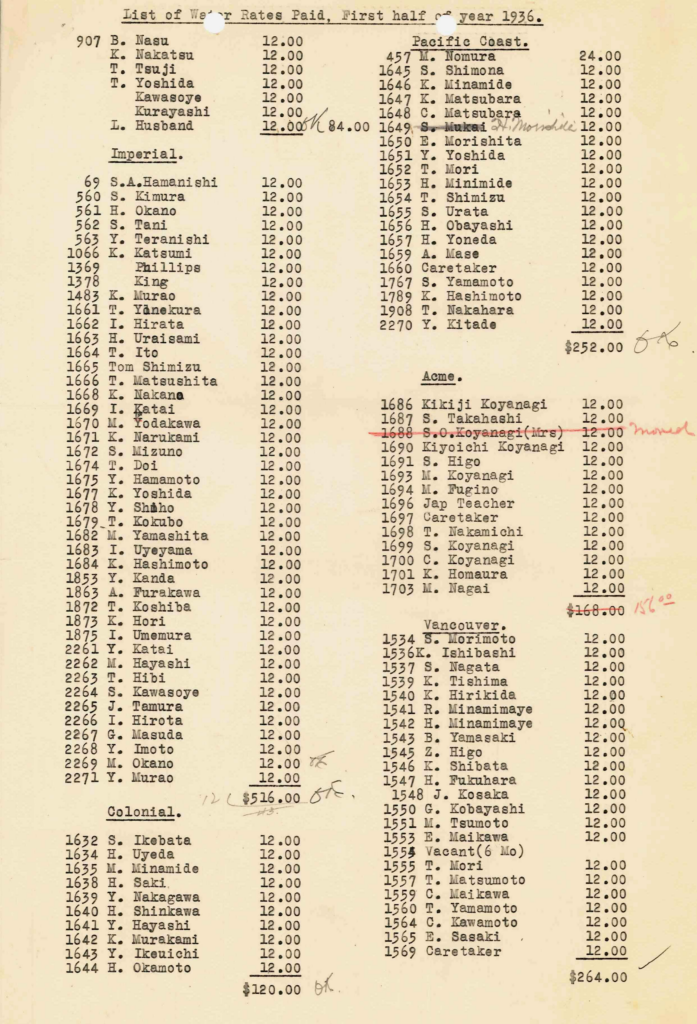

At Sea Island, near the mouth of the Fraser River, Japanese Canadian families lived directly beside canneries such as Acme and Vancouver Cannery. According to documentation compiled by the Sea Island Heritage Society, women and older children worked in the canneries during the salmon season while men fished or worked as engineers and boat builders.

Families built their own Japanese-language school because their children were excluded from public schooling.

Roy Nagata remembers Sea Island first through play. At low tide, he and his siblings would wander the sandbars, building sandcastles or rowing downstream to dig surf clams from the mud. When the tide returned, they shifted to the docks, diving from a board the community built themselves. Fall and winter were quieter, marked by basketball and the rare stretch of safe skating, when overflow from the dikes froze long enough.

Toshitsugu “Toshi” Koyanagi remembers the same sandbars, but with an edge of caution woven through them. Like other children growing up in cannery housing along the Fraser River, he spent summers playing where the tide pulled back the water and exposed the riverbed. His parents warned him constantly to be careful. Several drownings in earlier years lingered in community memory, reminders of what could happen to children living so close to the waterline.

Community newsletters later traced Toshi Koyanagi’s life through the full arc of the cannery world. As an adult, he worked on the Iona, a fish-collector boat that moved between small fishing vessels and Fraser River canneries, keeping the processing lines supplied. In 1942, like other Japanese Canadians on the coast, he was forcibly displaced during the Second World War.

The Pull of Market Consolidation

While workers followed the fish, ownership moved in the opposite direction.

The shift away from independent canneries didn’t happen all at once, and it didn’t happen evenly along the coast. But by the early 1900s, the logic was already clear: it was cheaper and easier for large firms to own many plants and decide, season by season, which ones were worth running.

On Sea Island, that shift came early. The Acme Cannery, established in 1899, was absorbed into the British Columbia Packers Association within a few years of BC Packers’ formation in 1902. Decisions about output, staffing, and even whether the plant would operate in a given year were no longer tied to the needs of the community living beside it.

At Kimsquit, consolidation played out differently, but with the same result. Remote canneries like Kimsquit were expensive to operate. Supplies had to be shipped in. Finished product had to be moved out by boat. When large firms controlled multiple plants, it made little sense to keep small, isolated operations running once larger, more centralized facilities could handle the same volume.

Through decades of mergers and restructuring, the assets and operations of BC Packers were absorbed into larger consolidated firms such as the Canadian Fishing Company (Canfisco), one of the last major vertically integrated fishing and processing firms in the province.

Where dozens of canneries once operated along BC’s coast, Canfisco now runs only a small handful of processing facilities, primarily in the Lower Mainland and Prince Rupert, alongside freezer plants and distribution centres.

A defining moment came in 2015, when Canfisco shut down its Oceanside cannery in Prince Rupert, marking the end of industrial-scale commercial salmon canning in the province. That closure led to the loss of hundreds of jobs and was widely seen as the culmination of decades of industry contraction.

A smaller commercial facility, St. Jean’s Cannery & Smokehouse in Nanaimo, continues to operate, processing wild-caught salmon and other seafood.

A Rupture Imposed by Policy

For Japanese Canadian cannery workers, the most devastating break did not come from fish or markets.

In 1942, the federal government ordered the forced removal of Japanese Canadians from the coast. Families were uprooted, boats confiscated, and access to fishing and cannery work severed. On Sea Island, archival records show residents evacuated and cannery housing later destroyed.

The experiences of fishing and cannery families after removal are preserved across museum archives, memoirs, and community histories documenting how displacement from the coast ended livelihoods that had defined generations.

One such account comes from the family of Grace Eiko Thomson, a writer and co-founder of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, who grew up in a Japanese Canadian coastal community before the war.

Grace’s mother, Sawae, recorded in her diary: “Manure clinging on straw hung stuck to these walls. A bare light bulb hung from the high ceiling. I stood in the middle of this barn, which was to be home to our family of six and couldn’t hold back the tears.”

Japanese Canadians were barred from returning to the coast until 1949, four years after the war had ended and long after boats had been sold, housing destroyed, and cannery work redistributed elsewhere.

The Work That Held the Coast

The Kimsquit photograph doesn’t show decline. It shows continuity: people walking into work because that’s what the day required.

Canneries are often remembered as heritage sites or industrial relics; less often as workplaces sustained by immigrant labour that was essential, seasonal, and poorly recorded.

The women in that photograph helped build a coastal economy. Their stories survive unevenly, in family records, community archives, and the spaces between official histories.