A federal effort has begun to transform B.C.’s controversial salmon farming industry over the next two years.

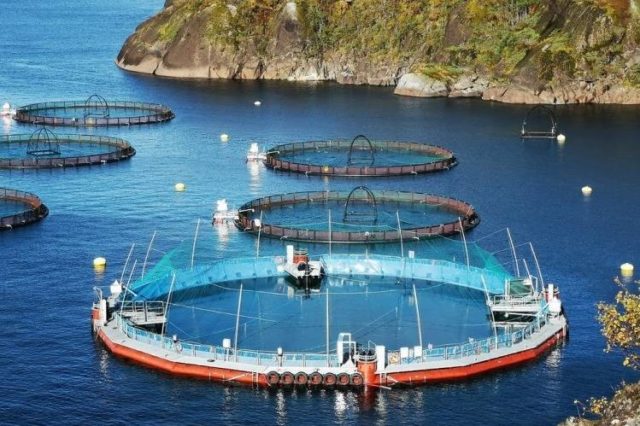

Scores of farms, raising imported Atlantic salmon in open ocean pens, have sprouted on BC’s coastlines over the past four decades. They produce food and jobs. But they’ve also become a political flashpoint, with opponents pointing to the negative impact of fish farms on struggling wild Pacific salmon, the environment, traditional commercial and recreational fishers, and tourism.

The issues all came to a head this summer, with federal licences for 109 salmon farms due to expire.

This week the federal government announced two-year extensions for 79 farms. The licences come with stronger conditions, to “help protect wild salmon stocks and their habitat,” said the statement.

And by early 2023, said fisheries minister Joyce Murray, the federal and BC governments, industry, and First Nations will begin working together on a plan to prevent domestic farm fish from coming in contact with threatened wild Pacific salmon, including by using land-based pens.

“We recognize the urgent need for ecologically sustainable aquaculture technology, and we are prepared to work with all partners in a way that is transparent and provides stability in this transition,” said Murray in the statement.

There’s a lot at stake: the welfare of coastal communities, the tourism industry, commercial fishers of wild salmon, fish farm workers, independent fish farmers, processors, the multinational corporations that own most of B.C.’s fish farms. And overriding them all is the decline of keystone Pacific salmon species, the subject of a massive Commission of Inquiry by Bruce Cohen 10 years ago.

Salmon farming in Canada creates some 14,500 jobs and $4 billion in “economic activity annually,” according to the aquaculture industry.

But ongoing scientific research warns of possible harmful effects on wild salmon. While most studies note the issues are complex, ranging from forestry practices in salmon spawning areas, climate change, and ocean pollution, peer-reviewed science reports suggest fish farms cause problems for wild salmon, from more parasitic lice to several diseases.

Scientist and environmental activist Alexandra Morton, who has fought to close B.C. fish farms for 30 years, welcomed the federal decision in a Facebook post: “I am impressed with this decision … It is a solid signal that the veil of farm salmon disease will be lifted and wild salmon will be free to reach the open ocean once again.”

The federal government said its key goals are to “lower potential risks for wild salmon by minimizing or eliminating interactions with salmon aquaculture,” attract more investment in aquaculture, including for land-based farms, and maintain “a competitive, viable salmon aquaculture sector that continues to generate jobs and investment.”

During the transition, the BC government stressed it wants “a comprehensive federal support plan for First Nations and communities that rely on salmon aquaculture for their livelihoods, as well as for exploring new technology and economic opportunities for the industry in these regions.”

Meanwhile the fate of as many as 19 salmon farms in the Discovery Islands – a sensitive migration route for wild salmon – remains in limbo. An attempt by the federal government to close them was overturned in April by the Federal Court.

Murray said the government is now holding talks about that zone with the province, First Nations, industry, and governments, and in January will decide on fish farms in the Discovery Islands.

The farms lie at the northern end of the Salish Sea and the eastern end of Johnstone Strait.