Heather Soo really, really, really likes fungi. She and her husband Kevin Soo both like mushrooms so much that their 2015 wedding featured a fungi theme.

When they married, in the forest of B.C.’s Strathcona Park, every table was named for a mushroom and decorated with specimens collected by the guests.

Some of us think of fungi as cremini mushrooms, fried up and served on a burger, perhaps. Soo laughs at that, and says she likes creminis, too: “Grocery store mushrooms are amazing!”

But fungi are about much more than all the “edibles,” she tells West Coast Now.

Heather Soo hosts several fungi walks each year on Vancouver Island for the public and for the Canadian Institute of Forestry, of which she’s a member. On Saturday, October 1, she will lead a walk at the Cumberland Fungi Fest.

She tells people that fungi are crucial to the environment, for example by connecting trees to nutrients in the soil. When tree seedlings are inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi, the new trees grow three or four times as tall as trees without the fungi, marvels Soo.

“Fungi grows on our skin, in our guts, in forest soils, in grasslands, and it plays such an essential role in all of life, that nothing at all would be here without fungi. And it’s cool, too!” she laughs.

The Soos both work in forestry, out of Campbell River. When they’re not working, they are often on fungi adventures, tramping through forests with their two little kids identifying mushrooms, or attending Fungi Festivals together. West Coast Now caught up with Soo as the family was leaving for the Bamfield Fungi Festival.

The Soos are not unusual in their passion: fungi is having a moment everywhere.

Fungi festivals are now found throughout the province, exploring what B.C. forest scientist Suzanne Simard helped discover, and has called the “Wood Wide Web.” That term refers to how trees communicate and help each other via vast underground fungi networks that benefit both plants and the fungi.

Simard’s work features in the hit documentary Fantastic Fungi on Netflix, as does another mushroom scientist, Paul Stamets, who has a central character named after him in the Star Trek series Discovery.

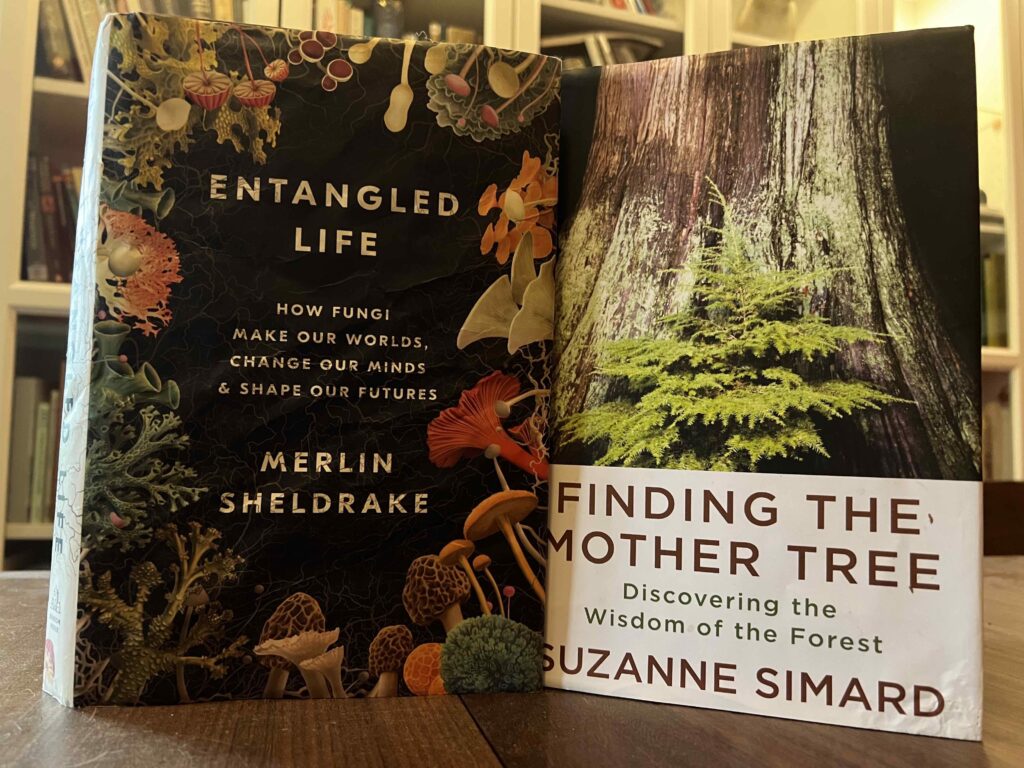

And B.C. has some of the most striking examples of fungi anywhere, writes British biologist and writer Merlin Sheldrake, who spends weeks in the province each year researching lichens, which are combinations of fungi and algae.

Sheldrake has an explanation for fungi’s popularity, he writes in Entangled Life, his best-seller about fungi. “Fungi provide a key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways that we think, feel, and behave,”

“Fungi are changing the way that life happens, as they have done for more than a billion years … They are eating rock, making soil, digesting pollutants, nourishing and killing plants, surviving in space, inducing visions, producing food, making medicines, manipulating animal behaviour, and influencing the composition of the earth’s atmosphere.”

Fungi do not fit in the familiar categories of plant versys animal, and instead have their own third “kingdom.” Their range is vast, from wee granules of yeast that we use to make bread, to honey fungi called Armilaria that can weigh hundreds of tonnes, sprawl over 10 square kilometres and live for thousands of years.

Ongoing research about fungi has enchanted Soo since she studied forestry at the University of British Columbia, graduating in 2010. “I’m really steeped in it and have been for a long time.”

Seven years ago, while listening to scientists at the Bamfield Fungi Festival, she decided to help spread the word about its marvels.

She’s quick to say that she’s a professional planning forester, not a mushroom scientist. “But I decided that I could do workshops on the introductory stuff.” She also promotes citizen science, asking people to join the social media network for naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists iNaturalist, and contribute sightings.

Asked to name her favourite mushroom, Soo laughs in delight. It’s the violet webcap – formally named Cortinarius Violaceus, easily found and abundant on the B.C. coast.. She laughs again and lowers her voice to a whisper: “Because it’s purple! It’s kind of fuzzy. It loves conifer (trees). It’s just like me!”