Passengers on the Duke Point to Tsawwassen last week caught an unusual sight. Two whales, one larger than the other, were spouting in the Strait of Georgia off the Gulf Islands.

But the passengers’ wonder at the wildlife quickly turned to concern as a boat approached the whales, passing within feet of them. “That boat’s going to run it over!” one person exclaims in a video captured of the incident.

Invasive boaters like the one seen here are becoming a growing problem on B.C.’s west coast. The pandemic encouraged lots of people to take up boating as a new hobby, but many of these newcomers don’t know the rules about safe marine engagement.

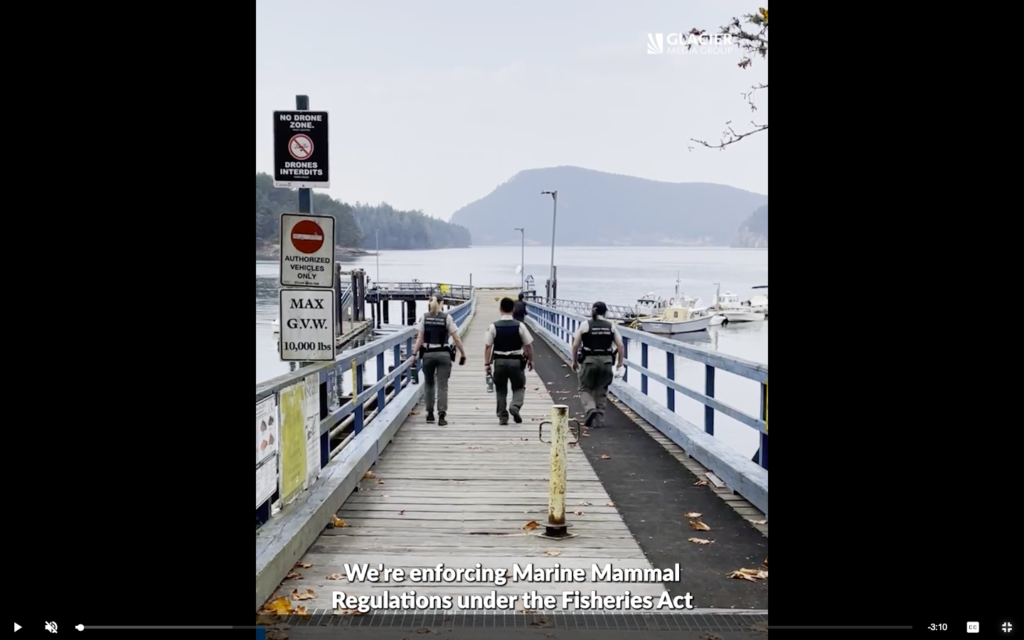

Thankfully, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has a new “whale police” force that looks out for the endangered creatures protected under the Marine Mammal Regulations of the Fisheries Act. The Whale Protection Unit is based in Victoria and Annacis Island near Delta, and its seven officers survey the seas and protect whales in a territory that spans 200 kilometres, from Campbell River to Ucluelet.

Officers like Scotti Griffin patrol the waters, keeping an eye on whales and warning offending boats to keep back 200 metres, off, sometimes with a loudspeaker and sirens.

“We have nearly seven-day-a-week coverage. But our area is quite large and to be on top of whales is a challenging thing. They move around,” she told The Times Colonist in an interview.

The Whale Protection Unit closely patrols sanctuary areas, like the interim sanctuary zone off Pender Island for endangered southern resident orcas whose population now totals only 73 whales. “On water presence is very important for us, to be part of the solution the southern residents, like, thrive in their population,” Griffin says in the video.

The unit is concerned mainly with the noises emitted by boats, which interfere with the whales’ echolocation and ability to find food and communicate. Toxins and pollution released from boats are also an issue, because they affect both the whales and the salmon the whales are trying to eat.

Most boaters will get away with a warning, and hopefully learn something new about boating guidelines put in place to protect the marine wildlife. But the Whale Protection Unit can collect evidence that leads to fines for bad boaters, from $2000 to $12,000 in the case of a diver who got too close to orcas in Prince Rupert Harbour.

Griffin, like most officers with the unit, is grateful for the chance to protect the marine mammals that she has been passionate about all her life. “It’s a lottery job,” she says to the Time Colonist. “Look at us today. We’re out here on a boat protecting whales!”