By Rochelle Baker, The Local Journalism Initiative, National Observer

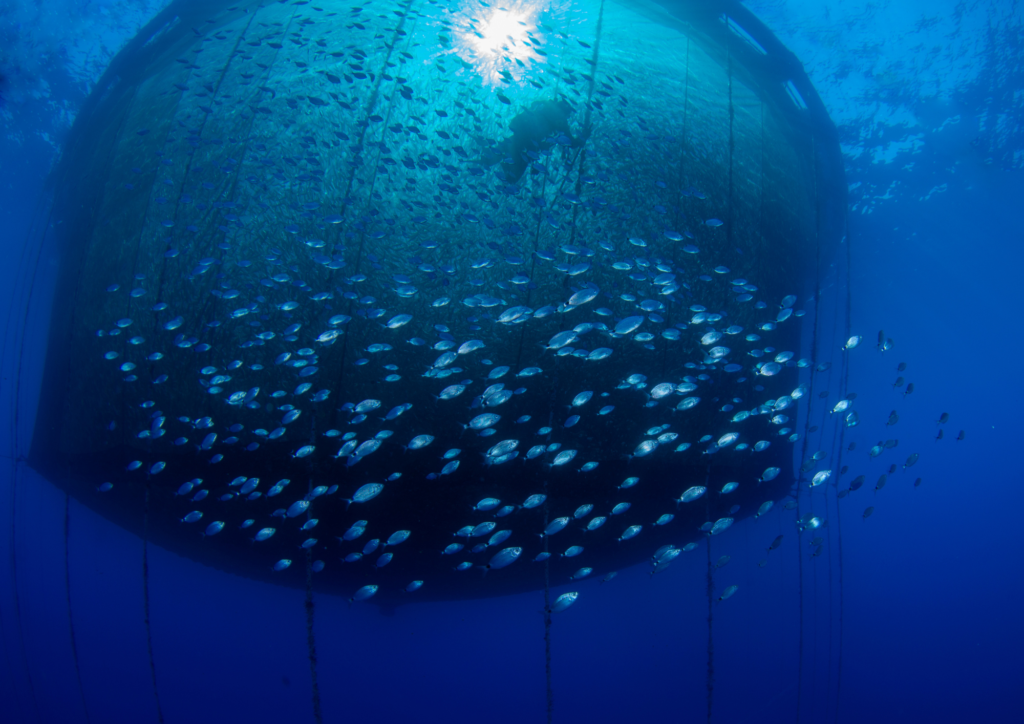

First Nations fighting to get salmon farms out of the ocean are dismayed in the wake of federal Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray’s recent engagement tour on a plan to transition open-net pen operations in B.C.

Murray spent much of last week visiting Vancouver Island aquaculture operations and meeting with First Nations, industry operators, wild salmon conservation groups and coastal community leaders in Campbell River and Port Hardy.

The federal Liberals’ 2019 election platform promised “to develop a responsible plan to transition from open-net pen salmon farming in coastal waters to closed containment systems by 2025,” which sent the salmon farming industry into a flap. Murray’s subsequent mandate from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is much the same, minus the reference to closed containment systems.

And after the minister’s visit, First Nations critical of salmon farms are convinced that what’s in the works is a watered-down version of Ottawa’s promise.

Rather than removing open-net pens by 2025, the minister is now talking about progressively minimizing interactions between farmed and wild fish, incentivizing innovations in aquaculture technology, tougher regulations for fish farm licences, and ensuring that area-based operations have First Nations partners.

The BC Salmon Farmers Association said the aquaculture sector is “heartened” after its round of meetings with Murray.

Operators are pleased Murray expressed interest in co-developing a transition plan, said Ruth Salmon, BCSFA interim executive director, in a statement.

A suite of tools and options are necessary to meet the needs of diverse marine ecosystems and the priorities of partner First Nations in whose territories they operate, Salmon said.

First Nations that want open-net pens out of the ocean feel the engagement process is flawed, and feel open-net pens aren’t going anywhere inside the next three years, said Bob Chamberlin, chair of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance.

“It’s simply a ‘go with the status quo.’ They’re just putting new laces on those old shoes,” said Chamberlin, who met with Murray along with chiefs from the K’omoks and Homalco First Nations, both opposed to open-net fish farms.

The intention of the meetings was to get input from a wide range of people, Murray told Canada’s National Observer after her tour.

It also provided the opportunity to clear up misunderstandings about the open-net pen transition process, she said.

She is aiming to develop “a pathway for existing aquaculture operations to adopt alternative production methods,” Murray said.

“So they can actually accomplish the goal of progressively minimizing or eliminating interaction between farmed salmon and the wild salmon.”

The goal is to have the transition plan in place next year and a new licensing regime devised by June 2024, said Murray. She did not give a final deadline for the process.

“I think there was some misunderstanding that there would be sort of a dramatic change in just a very, very short time,” she said.

ent production methods aren’t part of her mandate, Murray added, saying devising new farming methods would rely on the industry’s creativity and investment in emerging technology.

Large-scale aquaculture operators in B.C. have dismissed closed containment technology, arguing it isn’t advanced enough, requires a bigger energy footprint and is less profitable.

Instead, the sector is championing emerging semi-closed ocean systems — aimed at reducing sea lice and physical interactions between farmed and wild salmon. Or growing salmon longer in their land-based hatcheries before transferring them to open-net pens in the ocean.

Semi-closed systems, also in the development phase, are still semi-open, and do little to prevent waste, chemicals and diseases from impacting wild salmon, Chamberlin said.

Murray said all First Nations she met with in the region made clear they wanted a greater stewardship role and involvement in decisions around salmon farming in their waters.

“There were some First Nations that were clear about how important the industry has been to them in terms of jobs,” she added.

But Murray also needs to respect the aboriginal rights of the 100-plus First Nations in B.C. that rely on wild salmon and Ottawa needs to do what it promised, Chamberlain said.

“What about the value of food fish to all the nations in the Interior of British Columbia?” Chamberlain asked. “Because that has to weigh into the decision.”

Fisheries and Oceans Canada wrapped up public online feedback on the transition plan on Oct. 27.

This story by Rochelle Baker was originally published in Canada’s National Observer. It is republished under Creative Commons Licence according to the government-funded Local Journalism Initiative.